HOME / PROCLAMATION! MAGAZINE / 2012 / FALL / WILL YOU SEND YOUR OLDEST SON AWAY?

F A L L • 2 0 1 2

VOLUME 13, ISSUE 3

“Say you are my sister, that it may go well with me, because of you.” Sarai wryly remembered her husband Abram’s words as she stood watching the single file of Egyptian slaves walking past. Abram had made her tell this cowardly half-lie to protect him against powerful men who might otherwise kill him because of their desire for her. Sarai was, indeed, Abram’s half-sister, but more importantly, she was his beautiful wife. Because of their lie, an unsuspecting Pharaoh arrived to give Abram—not a death blow, but a generous dowry of servants and livestock in exchange for her (Gen. 12:16). She stepped into Pharaoh’s waiting litter and sighed, “You have been blessed, Abram, because of me, but our lie didn’t protect me from the harem.”

“Say you are my sister, that it may go well with me, because of you.” Sarai wryly remembered her husband Abram’s words as she stood watching the single file of Egyptian slaves walking past. Abram had made her tell this cowardly half-lie to protect him against powerful men who might otherwise kill him because of their desire for her. Sarai was, indeed, Abram’s half-sister, but more importantly, she was his beautiful wife. Because of their lie, an unsuspecting Pharaoh arrived to give Abram—not a death blow, but a generous dowry of servants and livestock in exchange for her (Gen. 12:16). She stepped into Pharaoh’s waiting litter and sighed, “You have been blessed, Abram, because of me, but our lie didn’t protect me from the harem.”

Abram failed to protect his wife, and Pharaoh wanted Sarai for himself—but God saw Sarai’s plight and rained horrific plagues on Pharaoh and his household (12:17). Pharaoh soon discovered the mistake in taking Sarai, a married woman, and rightly rebuked Abram for his lack of honor. The monarch lost no time in returning Sarai and firmly escorting Abram’s entire caravan out of Egypt to the desert where they began trudging back to drought-ravaged Canaan. In spite of Abram’s weakness and her own brush with danger, Sarai knew God had been good to them. They were returning to Canaan with an Egyptian fortune. Nevertheless, even this kingliest of gifts could never soothe the deepest ache in her heart—the longing to hold a child of her own.

Among Sarai’s new servants was an Egyptian girl who had apparently served in Pharaoh’s palace. And as a royal gift to Abram, she was likely very bright and attractive. We don’t know her original Egyptian name; we only know that her new owners called her “Hagar,” Hebrew for “Wanderer.” Serving Abram’s nomadic family, although they were wealthy, was a step down for a young woman who had served a king. Nevertheless, Hagar was eager to please and proved herself trustworthy so that Sarai appointed her as personal maid. This appointment was a position of honor, and Hagar served her mistress well for a time.

In her culture, slaves were considered the personal property of their owners, and usually slaves retained that status for life.1 Their children were also legally slaves, unless they could purchase their freedom. Occasionally, however, Egyptian slaves were allowed to own property, and some even married into their masters’ families. These privileged Egyptian slaves contrasted with other slaves throughout history who had little chance of advancement and were considered naturally inferior.2 In short, Hagar knew she had no hope of changing her status. She was destined to live out her life as a personal slave in a wealthy nomadic family.

Ten years passed after the Egypt incident, and Abram and Sarai remained childless. Though her father had named her “Princess,” Sarai could not live up to his hopes, nor to Abram’s. She said to Abram, “Behold now, the Lord has prevented me from bearing children. Go in to my servant; it may be that I shall obtain children by her” (Gen. 16:2). God had earlier promised them a son (Gen. 15:3-6), but she saw her barrenness as God’s excluding her from the promise. Now she wanted to do her part to make the promise come true. Hagar could “build up” the family as a surrogate mother.

Surrogacy was an accepted practice in those times for wealthy families with no heir. Sometimes they chose trusted servants to be their heirs,3 as Abram had chosen Eliezer (Gen. 15:2). In this case, Sarai esteemed Hagar, so she gave her servant to Abram as the second wife, and he agreed (16:3).

“And he went in to Hagar, and she conceived. And when she saw that she had conceived, she looked with contempt on her mistress. And Sarai said to Abram, ‘May the wrong done to me be on you! I gave my servant to your embrace, and when she saw that she had conceived, she looked on me with contempt. May the Lord judge between you and me!’” (Gen. 16:4, 5).

There was deep hurt in Sarai’s words. Abram had failed to protect her honor from Pharaoh and from years of shame. Now Hagar’s scorn added insult to the injury of being childless, and where was the justice in that?

Hagar was the new object of Abram’s affections, and she felt exalted over Sarai as the wife who had “built up” Abram. The child was legally Sarai’s, but who could not see who was the more blessed wife? The temptation of pride overcame this slave girl, and disdain for her mistress began to show. Sarai blamed Abram since his intimacy with Hagar had elevated her status. She had a grievance, and the law was on her side. Hammurabi’s Code stated that if a concubine acted as an equal to the first wife, she could be demoted back to slave status.4

This was an opportunity for Abram to lead his household with proper boundaries and loving reassurances. Instead of restoring peace, however, his passivity heightened the crisis. Abram withdrew himself from helping the battling women, so he said, “Behold, your servant is in your power; do to her as you please” (vs. 6). It was true; Sarai had charge over the female slaves including Hagar. Wounded Sarai was determined to put the upstart in her place, and she used Abram’s authority to “bow her down” with humiliating treatment.

“Then Sarai dealt harshly with her, and she fled from her” (vs. 7).

Sarai’s wrath was intolerable for proud Hagar, and she quickly made her decision. She threw together a few necessities, and under cover of darkness, she fled into the desert.

The Messenger

The desert was vast, and Hagar was ill-prepared for such a long journey, but her anger was still hot. She kept pressing on through the night, walking for hours under the stars, and she began to examine her life.

I wish I had never left Egypt to live in this god-forsaken desert. I belong with my own people so my child can be Egyptian, like me!

It felt so good to be free! Sarai couldn’t find her—in fact, no one could. She had to admit to herself, though, that this wilderness was dangerous for her, a lone, pregnant woman. There were hidden things that could leap out and bite her. She could fall down a cliff, or into the hands of evil men. Nevertheless, pride and rage drove her over hills and through valleys, heading southwest. Her water and food would soon run out, she knew, but she remembered a little spring on the way to Shur. As the sun rose, she searched the rocky hills for any hopeful sign, but the empty brown landscape seemed to go on forever. Several days later she tipped back the water skin and drank the last drops. Weary and stumbling—despairing—she suddenly saw the familiar cluster of green bushes that encircled the elusive pool. Now she could be refreshed for the rest of her journey! After a long drink, her thoughts drifted off again to her homeland.

Where are the gods of my people? Where is Horus, with his all-seeing eye, to see me and protect me? Can he help me all the way out here?

Hagar was alone, but she was happy to have fled Sarai’s oppression—with her strange God who whispered in the dark to the old man. What grand promises He had made! And then her thoughts returned to her fading hope of reaching Egypt. If she ever got there—if she found her former taskmasters and begged for mercy, would they take her back, a runaway slave? Her own family was too poor to help her, if they were still alive. And what would happen to her baby?

Pharaoh traded me away like a sheep for that woman; I don’t belong to him anymore. In fact, no one wants me; I have no people.

She sat by the pool with her doubts while a hot desert wind blew sand into her eyes and mouth. She had never felt more utterly lost and alone.

I am no one; I am invisible, and I may as well be dead.

“Hagar!” The voice was a gentle, kind voice, but with ground-shaking power. Frightened, she looked about, and saw no man. Who could possibly know her Hebrew name in this remote place? Then she saw Him, and she knew this was no man, but Someone of terrifying, wonderful majesty. He drew near to her, and she fell to the ground.

“Hagar, servant of Sarai, where have you come from and where are you going?” (vs. 8) He had found her! It was no use lying to Him. “I am fleeing from my mistress Sarai.”

He was the “Angel of the Lord,” ma’lakh Yahweh, and the Messenger of the Covenant. He appeared as the protector of His people in their darkest hour. His voice had called Abram out of Ur, and long ago He had called the galaxies into existence by the word of His power. Now He had words for His angry slave girl. “Return to your mistress and submit to her” (vs. 9).

Submit? Do I have to return to that jealous woman?

Of all the things Hagar most dreaded, returning and submitting to Sarai topped the list. But that wasn’t all. He said, “I will surely multiply your offspring so that they cannot be numbered for multitude” (vs. 10).

Multiply offspring…multitude? This must be Abram’s God, that is his talk.

Then He said, “Behold, you are pregnant and shall bear a son. You shall call his name Ishmael (God Hears), because the Lord has listened to your affliction” (vs. 11).

He hears! Surely He knows all my sorrows.

He also said to her, “He shall be a wild donkey of a man, his hand against everyone and everyone’s hand against him, and he shall dwell over against all his kinsmen” (vs. 12).

Hagar understood the donkey imagery. She had grown up with the onager, the wild ass of the desert that no man could tame. God spoke of His donkey to Job:

“Who has let the wild donkey go free? Who has loosed the bonds of the swift donkey, to whom I have given the arid plain for his home and the salt land for his dwelling place? He scorns the tumult of the city; he hears not the shouts of the driver” (Job 39:5-7).

For His sovereign purposes, God determined that Ishmael would live as an unruly man in perpetual conflict, “dwelling over against all his brethren.” Ishmael’s nation, although destined for greatness (Gen. 17:20; 21:18), was also destined to exist in perpetual conflict, especially with his brothers. This was their divinely appointed role in history.5

With that, He vanished. Hagar was overcome with delight and wonder at the One she had just seen. “You are a God of seeing,” for she said, “Truly here I have seen him who looks after me” (vs. 13). She looked up again to the dry hills and saw them with new eyes. This place of death had been transformed into a place of glory. He had followed her here! He was watching over her right now. She suddenly realized:

That was Abram’s God! This place belongs to Him, every stone, every snake and scorpion. I belong to Him too! She named the place, Beer-lahai-roi, “Well of the Living One Who Sees Me.”6

Did Hagar belong to the true God? While we cannot make a final judgment, consider that the Lord heard her affliction and pursued her into the wilderness. He met this troubled woman at the well and knew everything she had ever done (Jn. 4:39). He satisfied her thirst. When He sent her back to submit to her enemy, she obeyed because she believed His promises. He knew His lost sheep; she heard His voice, and she followed Him (Jn. 10:27). “Is He not the God of the Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also” (Rom. 3:29).

Hagar got up, filled her water bottle, and turned her back on Egypt. The long, rocky road back to Abram’s tents didn’t seem so treacherous, for she was not alone. She carried His words and little Ishmael with a great future. Inevitably, the dreaded moment arrived when she stood before Sarai, but she remembered His words, and she submitted. She also told Abram and Sarai her story. She had met the God Who Sees, and He had named her baby Ishmael, “God Hears.” They believed her, and when the baby was born, Ishmael he was. Thereafter, whenever Abram and Sarai heard Ishmael’s name called, they were reminded that God heard their affliction, too.

As For Sarai Your Wife

“When Abram was ninety-nine years old the Lord appeared to Abram and said to him, “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless…” (Gen. 17:1).

These commands to Abraham were not conditioned on his perfection; rather they were Abraham’s promised responses to God’s faithfulness. Genesis 17 recounts how God renewed His covenant with Abram to bless and multiply his offspring, and He changed his name to Abraham. God also commanded him to circumcise all the males of his household, and Abraham obeyed that same day. Then God said,

“As for Sarai your wife, you shall not call her name Sarai, but Sarah shall be her name. I will bless her, and moreover, I will give you a son by her” (Gen. 17:15).

All along, even when she had felt shamed and forgotten, God had kept anxious Sarah in His plans as His “princess,” for she was blessed as Abram’s true wife. Because she had been barren, giving birth would glorify God all the more. When God spoke these words, Abraham fell on his face and laughed with amazement. Ninety-year-old Sarah heard his laughter from behind the tent door, and she also laughed quietly to herself. The Lord asked, “Why did Sarah laugh? Is anything too hard for the Lord?” She denied laughing, but He said, “No, but you did laugh” (Gen. 18:15) Sarah forgot; God hears.

“The Lord visited Sarah as he had said…and Sarah conceived and bore Abraham a son in his old age at the time of which God had spoken to him” (Gen. 21:1, 2).

Sarah held baby Isaac in her aging, tired arms, and laughed out loud, saying, “‘God has made laughter for me; everyone who hears will laugh over me.’ And she said, ‘Who would have said to Abraham that Sarah would nurse children? Yet I have borne him a son in his old age.’”

The baby grew. “And Abraham made a great feast on the day that Isaac was weaned. But Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had borne to Abraham, laughing.” Isaac was between two and three years old, while Ishmael was about 16. The original language indicates that the laughing was continuous behavior,7 and in Galatians 4, Paul interprets the “laughing” as mocking Isaac. Sarah saw her opportunity and went to Abraham saying,

“Cast out this slave woman with her son, for the son of this slave woman shall not be heir with my son Isaac” (Gen. 21:10).

Abraham was horrified, for Ishmael was his precious firstborn, and Hagar was close to his heart. “But God said to Abraham, ‘Be not displeased because of the boy and because of your slave woman. Whatever Sarah says to you, do as she tells you, for through Isaac shall your offspring be named. And I will make a nation of the son of the slave woman also, because he is your offspring’” (Gen. 21:12, 13).

Although Sarah was moved by jealousy to expel Hagar and her son, nevertheless the inheritance could not be shared. Furthermore, God supported Sarah, reassuring Abraham of His promises regarding Ishmael. Significantly, God did not call Hagar “wife,” but “your slave woman.” Hagar could never be Abraham’s true wife because Sarah was his original bride. Moreover, Ishmael was the child of human devising. God’s words were awful to bear, but Abraham obeyed.

Abraham got up early the next morning and gave Hagar and Ishmael provisions for their desert journey. They must have tearfully rehearsed the promises that God had made for Ishmael, trusting that He would care for His own. For all his wealth and power, Abraham’s promises to them had all come to nothing, and there were few words to say for such a painful parting. The sun would soon be hot, and they had to go.

Mother and teenaged son began walking south, but not towards Egypt. They entered the Beersheba wilderness where their carefully rationed water would last only a few days. They had to keep moving, searching for any sign of water, but they found none. They walked until teenaged Ishmael became so weak he kept falling down. He was too big for her to carry, and in her exhaustion, she finally “threw” him under the shade of a desert bush. She could no longer help him; the water was gone, and they were near the end. Hagar walked a few hundred feet away and sat down, facing the other way. She couldn’t bear to hear his cries and said aloud, “Let me not see the child die” (Gen. 21:16). Then she lifted up her voice, and wept.

Out of the blazing sky came the Voice: “What troubles you, Hagar? Fear not, for God has heard the voice of the boy where he is. Up! Lift up the boy and hold him fast with your hand, for I will make him into a great nation” (Gen. 21:17, 18). The Messenger of Abram’s Covenant was still watching Hagar as He had promised years before. Now, when she looked across the sand, He opened her eyes to see a hidden well. God had carefully guided them to that very spot. Water! She filled her skin and ran over to pale, gasping Ishmael and pressed the water to his lips.

“And God was with the boy, and he grew up. He lived in the wilderness and became an expert with the bow. He lived in the wilderness of Paran, and his mother took a wife for him from the land of Egypt” (Gen. 21:19-21).

As a child of unbelief, Ishmael would develop a fierce, independent spirit. He married the Egyptian wife his mother fetched for him, and she bore him 12 sons who established themselves in the Sinai desert as a restless culture of warring tribes (Gen. 25:12-18). It was never God’s design for Hagar and Ishmael to coexist with Sarah and Isaac in Abraham’s tents. By sovereign design Hagar’s expulsion fit in with God’s promise to Abraham that through Isaac all the world would be blessed through his Seed. Now through that promised Seed, Hagar’s and Ishmael’s descendants as well as all the rest of us Gentiles can be adopted into Abraham’s family.

God expanded Ishmael’s nation as promised, but throughout their history the Ishmaelites were idolatrous. Hagar’s Arabian descendants adopted many deities, including Hubal and the goddess Al-Lat. The massive agate statue of Hubal, the lunar Lord of the Ka’bah, stood in Mecca where animal and child sacrifices were offered to him.8 By the time of Paul, Ishmael’s descendants’ polytheism was well established. Ironically, in 630 AD, Mohammed purged Mecca of its 360 idols to make a holy place for Allah.9 By the sword of Mohammed, Islam violently conquered Hagar’s sons, and of all religions, none demonstrated the lash of religious law more sharply than Islam’s Sharia law. As Salman Rushdie, a modern fugitive from Islam said, in that religion there are “rules for every damn thing.”10 In spite of its assault on polytheism, however, Islam’s religious law has not delivered Ishmael’s descendants from their wild and warring ways. In spite of Islam’s monotheism, we see in it the evidence that of all humanity’s dark impulses, none is more dangerous than religiosity separated from the God of Abraham.

The Ishmaelites, however, living in Arabia in the Sinai desert, were not alone in their pattern of bondage. To the north, their Jewish brothers in Jerusalem also labored in bondage under Sinai’s long shadow.

Listening to the Law

The Galatian Christians had been liberated from their idolatry by the gospel but had become discontented. Although they had abandoned their pagan idols for faith in Christ and were adopted as sons and had received the Holy Spirit and experienced His power, they wanted more. They coveted Jewish blessings which they were told would come with keeping the law. If God awarded greater kindnesses to sons of the law, as the Judaizers suggested, then Sinai would be their covenant, too. So Paul asked them,

“Tell me, you who desire to be under the law, do you not listen to the law?” (Gal. 4:21).

Then he showed them from the Torah that living under the law and worshipping idols were both varieties of slavery (Gal. 4:9).

“For it is written that Abraham had two sons, one by a slave woman and one by a free woman. But the son of the slave was born according to the flesh, while the son of the free woman was born through promise. Now this may be interpreted allegorically: these women are two covenants” (Gal. 4:21-24).

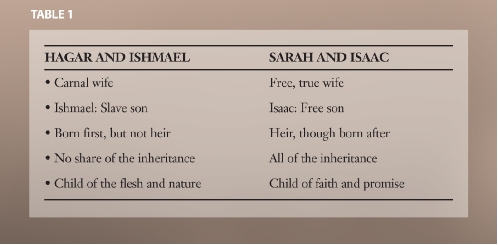

Abram and Sarai had contrived to fulfill God’s promises by natural means. Their scheme produced a child of human effort and will, so he was born of nature instead of faith. In reality, the marriage of Abram to his slave was prompted by a loss of confidence in God, so Ishmael was misbegotten into slavery. In contrast, Isaac’s birth was a miracle through faith, not through his parents’ working or conniving, and he lived by trusting God’s promises.11 As a child of nature, Ishmael was “a wild donkey of a man,” resisting authority and fighting for survival. Thus the two covenants represented by Hagar and Sarah’s sons contrast living by faith in God’s promises vs. trusting in self (See table 1).

Abram and Sarai had contrived to fulfill God’s promises by natural means. Their scheme produced a child of human effort and will, so he was born of nature instead of faith. In reality, the marriage of Abram to his slave was prompted by a loss of confidence in God, so Ishmael was misbegotten into slavery. In contrast, Isaac’s birth was a miracle through faith, not through his parents’ working or conniving, and he lived by trusting God’s promises.11 As a child of nature, Ishmael was “a wild donkey of a man,” resisting authority and fighting for survival. Thus the two covenants represented by Hagar and Sarah’s sons contrast living by faith in God’s promises vs. trusting in self (See table 1).

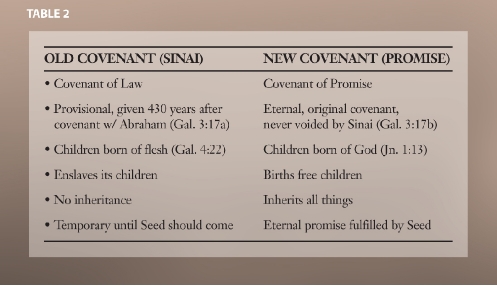

“One is from Mount Sinai, bearing children for slavery; she is Hagar” (vs. 24b). Just as Ishmael and Isaac could not coexist in one tent, so law and grace are two covenantal systems that produce opposite results. Slavery and freedom cannot live together in one system (See table 2).

“One is from Mount Sinai, bearing children for slavery; she is Hagar” (vs. 24b). Just as Ishmael and Isaac could not coexist in one tent, so law and grace are two covenantal systems that produce opposite results. Slavery and freedom cannot live together in one system (See table 2).

The law was not everlasting but was given as a temporary measure for Israel (Gal. 3:17). Now that faith has come, the first covenant of law has been outlawed (Gal. 3:25). Placing ourselves under the shadow of Sinai’s law, instead of under the authority of the One who fulfilled the law, contrives an illegitimate religion that only gives birth to lawlessness.

In the house of Abraham, Hagar and Ishmael’s purpose was to serve their masters. Yet in spite of their service and even in spite of Ishmael’s biological connection to Abraham, Ishmael hoped in vain for his father’s inheritance. Likewise, law is the slave of grace; the two will be in conflict, for law has no part in grace’s inheritance. Therefore, the two covenants of law and grace cannot live in the same house.

“Now Hagar is Mount Sinai in Arabia; she corresponds to the present Jerusalem, for she is in slavery with her children” (vs. 25).

Mt. Sinai and its laws are in Arabia, outside the land of promise, and that is where the sons of Ishmael have lived since the days of Hagar. Paul understood that once the new covenant of grace was inaugurated by the blood of Jesus, his Jewish brothers in Jerusalem were also in bondage, refusing to believe in Jesus as the reality that fulfilled the law’s requirements and insisting on still keeping the law to earn Abraham’s inheritance. In other words, Hagar’s slavery to the works of human flesh corresponds to Jerusalem’s slavery to physical servitude under the law. The Judaizers who sought righteousness through adding the law to the gospel were reenacting the envious, slavish resentments of both Ishmael and Jerusalem.12 In this metaphor, Paul says both the descendants of Ishmael and the descendants of Isaac insisted on staying in control through their own acts of the flesh. Neither was willing to trust God alone.

As long as he remains in the house, Ishmael will mock Isaac. Hagar and Ishmael must be cast out.

“But just as at that time he who was born according to the flesh persecuted him who was born according to the Spirit, so also it is now. But what does the Scripture say? ‘Cast out the slave woman and her son, for the son of the slave woman shall not inherit with the son of the free woman’” (vs. 29, 30).

Spirit of Slavery vs. Spirit of Adoption

We have two world views from which to choose. Under the first, we devise a system to earn our spiritual inheritance. We attempt to please God or natural forces by pursuing rules of good living. Alternatively, we see the majesty of God’s grace; we despair of our own slavish virtue, and we accept the gospel of Christ’s finished work. When we believe in the Lord Jesus’ death and resurrection for us, we are reborn, not by our willing or working, but of God as new creatures (Jn. 1:13).

Of course, that sounds terribly impractical—and it is. The gospel does not begin with practical advice, but with a radical disruption of our proud, slavish lifestyle. Jesus said, “The slave does not remain in the house forever; the son remains forever” (Jn. 8:34, 35). The lawful slave is never secure as a member of his master’s household and always lives under threat of being cast out. Slaves are human commodities who must continually prove their worth to earn their blessings. The shrewd slave “knows his place”: he never attains his dreams but struggles to get what it seems should be his. As humans, we naturally serve the ruler of this world, and we love our rebellious, grasping ways. As natural slaves in the domain of darkness (Col. 1:13), we haven’t just broken some rules; we have committed treason against our Creator, the sovereign God over all. Until we believe in the Lord Jesus, we are slave children like Ishmael.

In contrast, the adopted sons know that they are adopted through their Father’s grace. Their value is not tied to their performance, measured in units of labor, but is established by a single “unit” of Christ’s obedience unto death. Moreover, just as natural slaves know their place to be continual subservience, the sons of God know their place too: “in Christ,” having His life, forever. When we believe in the Lord Jesus, His life and death are ours; we are freed. We are miraculously born of God, and like Isaac, we are children of promise. From that moment we are secure forever as permanent members of His household. We are never cast out (Jn. 6:37), for when the Son sets us free, we are free indeed (Jn. 8:36).

In Luke 15, Jesus also contrasted two sons. The younger son was wayward but accepted by grace, while the older son was proudly resentful like an obedient slave. He appeared obedient on the outside, but in his spirit, he resented his father as the commandment-giver (vs. 29). As Ishmael had undoubtedly felt, the older son in the parable felt entitled to the inheritance, and he resented his father for never giving him even a goat. The father replied, “You are always with me, and everything I have is yours!” But the older son didn’t want his father’s grace; he believed his labor proved his worth, and he wanted his wages.13 In contrast, the children of grace are like the younger son who returns to the Father’s house and abides there by grace alone. When the Father’s grace makes us sons at heart, we obey Him from the heart and no longer work for wages.

The Oldness of the Letter

Teaching our children morality requires clear, specific rules. For them, virtue must be broken down into the smallest units of behavior, just as kindergartners learn to read one letter at a time. In Galatians 4:3, Paul calls these moral details stoicheia, or “elemental principles,” rules for little children. We begin children’s morality lessons simply with, “No hitting or kicking!” and then, “No biting or pinching!” and so on. According to Paul, Christians who want to live under the law are under basic prohibitions as are toddlers and slaves. When we become fully sons, Paul said, we are no longer under such “weak and worthless elementary principles.” Such a way of life does not produce righteousness, but infantile, slavish compliance, “the old way of the written code” (Rom. 7:6).

We know that the law (which is not defined by the 10 Commandments but is, rather, the entire Torah) is good when used lawfully and was laid down for the lawless and unholy (1 Tim. 1:8,9). Many people, however, do not understand that the Ten Commandments elegantly reduce the 603 other commandments in the Torah into a succinct summary. In other words, the Ten Commandments were never intended to be a stand-alone document.

The law-keeper, however, believes that the Ten Commandments are his only trustworthy restraint against sin. He reasons that because good laws foster peaceful relationships and a civil society, his fleshly nature will be suppressed by scrupulous law-keeping. Sons of the law, which they define as the Ten Commandments, disdain others who don’t live under the law as irresponsible and unholy. For them, obedience is imitating Jesus, their supreme example of righteousness-by-law, rather than their Substitute.

Laws restrain behavior, but they cannot restrain desires (Col. 2:20-23). They only excite our worst passions (Rom. 7:8). Our sinful natures use the law to stir up our natural rebellion to more willful sins (Rom. 7:7). Instead of the law producing righteousness, therefore, our flesh perverts the law into an instruction manual for more civil, respectable sins. The Pharisees paraded their legally correct behaviors to exalt themselves. Similarly we observe the laws we like and avoid those “least commandments” (Matt. 5:19) that we don’t respect. When we use our own “Sinai-Lite” to scratch our religious itch, we show our contempt for the entire law (Jas. 2:10). Consequently, placing ourselves under any part of Mosaic law obligates us to all of it, and none of us can place ourselves under any part of the law without failing and being cursed (Gal. 3:10). Working for the law only increases our debt:

You load sixteen tons, what do you get

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store.14

God brought laws into human history for a specific function, to “increase the trespass” (Rom. 5:20). The law was added because of human transgressions (Gal. 3:19) to drive us in desperation to our knees and to seek Him in repentance. The very law that promised life will only prove death to us (Rom. 7:10). The old written code carved in stone is rightly called the “ministry of death” (2 Cor. 3:7). What was designed to stir up sin in us cannot be used to suppress sin. “The very commandment that promised life proved to be death to me” (Rom. 7:10).

The whole law, including its animal sacrifices and ethical commands, are a constant reminder of human weakness and cannot cleanse the conscience (Heb. 10:1-3). The Decalogue can no more make us holy than can shedding the blood of bulls and goats. There is no law that can give life, so righteousness cannot be through the law (Gal. 3:21). Our best law-keeping produces no more life than does killing a sheep, walking to Mecca, or stoning the Devil.

The Newness of the Spirit

Considering all this, we have to ask ourselves, what is the object of our deepest attachment and devotion? To what or whom are we married? Cohabitation with the law is a very bad marriage—so bad, in fact, it is worth dying to escape:

“Likewise, my brothers, you also have died to the law through the body of Christ, so that you may belong to another, to him who has been raised from the dead, in order that we may bear fruit for God. For while we were living in the flesh, our sinful passions, aroused by the law, were at work in our members to bear fruit for death” (Rom. 7:4,5).

Christians are not married to a thing, even the holiest thing, but to a Person. Like Abraham who tried to help God keep His promise by taking the slave Hagar as a second wife, we naturally try to gain God’s blessings by working hard to please Him. When our best efforts fail to bring the blessings to which we feel entitled, we can learn what to do by looking again at Abraham. He finally believed God and trusted Him to fulfill His original promises through Sarah, and God blessed the entire world. Abraham’s marriage with Hagar was like Sinai’s laws, “weak and useless” (Heb. 7:18-19), and ready to vanish away (Heb. 8:13). But when Abraham and Sarah trusted a living Person who made better promises than their own efforts (Heb. 8:6), they received God’s promise even though their bodies were “as good as dead” (Rom. 4:19). Likewise, when we turn from our works of the law and the flesh to Him, we are given to the living God. Then our torrid affair with the law, like Abraham’s embrace of Hagar, must end so we can trust Him and give all our devotion to Him. We bear fruit for God after we die to ourselves—and to the law.

“But I say, walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the flesh” (Gal. 5:16). When we are led by the Spirit, we are not under the law (vs. 18). Contrary to what many of us were taught, walking in the Spirit does not equal Spirit-powered law-keeping. Instead, walking by the Spirit means we are spiritually alive instead of dead, and we are able to trust God’s promises and submit to them. He works in us both the willing and doing. We don’t die to the law only to marry it again (Rom. 7:4) and revive the deadly law-flesh partnership. Sanctification is by faith in God’s grace alone, from start to finish. No matter how hard things get, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9). We are free from the law, not to serve the flesh, but to fulfill it this way: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Gal. 5:14).

We are either children of the slave woman or children of promise. We are born as indebted slaves by nature—until we believe in the Lord Jesus as the fulfillment of all God’s promises. He adopts us, and we become children of His promise. Our mountain of legal debt was paid in full with blood, once for all. Our law-keeping cannot earn, or keep, what He has promised. Say farewell to hard labor under Sinai’s shadows, and rest on His better promises guaranteed by Jesus’ blood.

Surrender your need to please God and discover what Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar experienced; the God who sees keeps on caring for you. His promises are sure, and He has secured your eternal future through the blood of Jesus. “Cast out the slave woman and her son, for the son of the slave woman shall not inherit with the son of the free woman” (Gal. 4:30).

In Christ we are free indeed! †

Endnotes

- Ayman Fadl, Egyptian Slavery, http://www.aldokkan.com/society/slavery.htm

- Andre Dollinger, Slavery In Egypt, http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/timelines/topics/slavery.htm

- Dollinger, Ibid.

- Bob Deffinbaugh, “When Women Wear the Pants,” http://bible.org/seriespage/when-women-wear-pants-genesis-161-16.

- H. C. Leupold, Exposition on Genesis, p. 245, linked at PreceptAustin, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/leupold/genesis.xviii.html

- Ibid.

- Leupold, ibid, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/leupold/genesis.xxiii_1.html.

- Timothy Dunkin, Ba’al, Hubal, and Allah, http://www.studytoanswer.net/islam/hubalallah.html.

- Karen Armstrong (2000,2002). Islam: A Short History, cited at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaaba.

- Salman Rushdie, Is Nothing Sacred? http://www.beartronics.com/rushdie.html.

- G.G. Findlay, The Epistle to the Galatians, pp. 290-291, linked at PreceptAustin, http://books.google.com/booksid=LTMaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA291&output=html.

- Findlay, Ibid., p. 295.

- John Piper, The Blinding Effects of Serving God, Sermon, September 3, 1995, http://www.desiringgod.org/resource-library/sermons/the-blinding-effects-of-serving-god

- Merle Travis, 16 Tons, http://www.cowboylyrics.com/lyrics/classic-country/sixteen-tons---tennessee-ernie-ford-14930.html

Copyright 2012 Life Assurance Ministries, Inc., Casa Grande, Arizona, USA. All rights reserved. Revised October 2, 2012. Contact email: proclamation@gmail.com

Martin L. Carey grew up as an Adventist in many different places, including Tacoma Park, Maryland, Missouri, and Guam, USA. During daylight hours he works as a psychologist for a high school in San Bernardino, California. He is also a licensed family therapist. He is married to Sharon and has two sons, Matthew, 10, and Nick, 24. He continues to pine for clear, dark skies with eight different telescopes up to 20”. Biblical research and classical piano take up his remaining energy. You may contact him at martincarey@sbcglobal.net.

Martin L. Carey grew up as an Adventist in many different places, including Tacoma Park, Maryland, Missouri, and Guam, USA. During daylight hours he works as a psychologist for a high school in San Bernardino, California. He is also a licensed family therapist. He is married to Sharon and has two sons, Matthew, 10, and Nick, 24. He continues to pine for clear, dark skies with eight different telescopes up to 20”. Biblical research and classical piano take up his remaining energy. You may contact him at martincarey@sbcglobal.net.